A language in constant flux: Provoke and contemporary photography

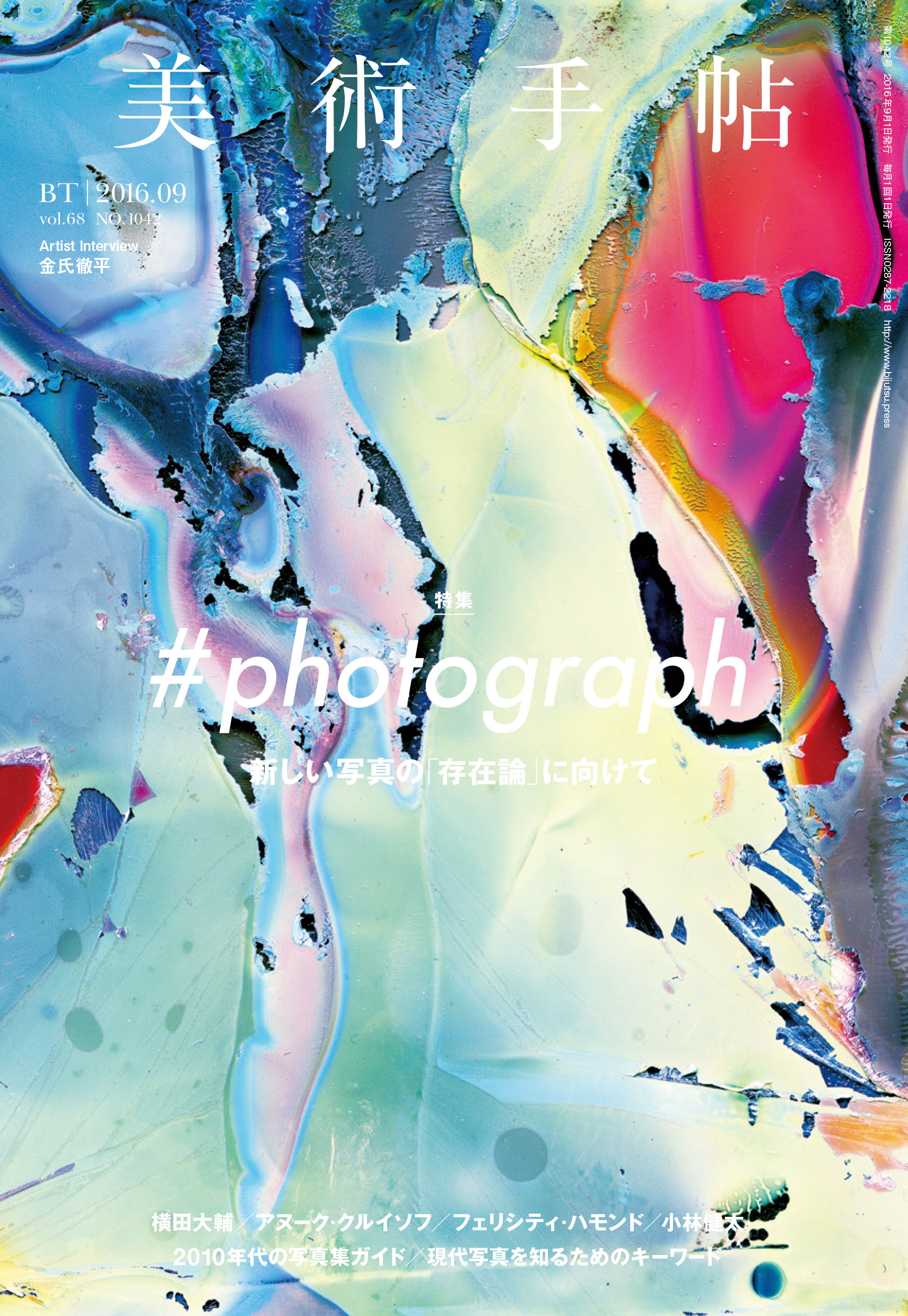

Bijutsu Techo, Vol. 68, September 2016

I contributed an essay to the September 2016 issue of the art magazine, Bijutsu Techo, looking at the influence of the Provoke movement of the late 1960s-early 1970s on contemporary photographers.

In recent years a series of major exhibitions—Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant Garde (MoMA, 2012), For a New World to Come (Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2015), and most recently Provoke: Between Protest and Performance which is currently touring in Europe—have focused on a particularly turbulent and dynamic period for the Japanese art scene that ran from the 1960s into the 1970s. In each of these exhibitions, Provoke, the magazine first published in 1968, plays a central role. Despite its short lifespan and limited circulation, it is now recognized as one of the key moments, or indeed movements in twentieth century Japanese photography.

The recent interest in Provoke and its avant-garde peers, begs the question of their relevance to contemporary photography. Beyond a search for Provoke’s direct descendants (perhaps too much has been made of the links with Daisuke Yokota’s work in this regard) it is interesting to consider how the ideas posited by Provoke are being used today.

Commonly associated with the are, bure, boke (rough, blurry, out of focus) aesthetic that characterized much of its photographic output, Provoke’s significance went far beyond the development of an aesthetic. The group articulated its revolutionary ambitions in detail in a manifesto highlighting the inadequacy of the prevalent photographic language in the face of a new world order. The multiple concerns laid out in this manifesto (materiality, the relationship between images and language, the photographer’s fragmented experience of the world, etc.) convinced the Provoke artists of the need to redefine the language of photography in order to create new ideas.

While Provoke arose in a specific, highly charged political context that is difficult to compare to present day Japan, let alone further afield, significant parallels exist with the “existential crisis” that is currently gripping photography, largely driven by the way that digital technologies have fundamentally transformed the medium and the world around us. Major photographic institutions around the world from SFMOMA to the ICP in New York, have recently placed the question of what photography is—and what it will become—at the heart of their programming. A number of contemporary artists, both in Japan and overseas, have responded to this question by seeking to develop what could be described as a new photographic language, just as Provoke did fifty years ago.

The work of the London native Anthony Cairns echoes many of Provoke’s concerns. Cairns is a quintessentially urban photographer: his projects are often named after the city or postcode of the location they depict. Beyond an evident aesthetic kinship, Cairns’ work extends Provoke’s attempts to translate the urban experience into images. Just as Yutaka Takanashi or Daido Moriyama depicted the gritty, unstable nature of urban life in 1970s Japan, Cairns uses a similar aesthetic to capture the glitchy, 24/7 buzz of today’s cities.

While the are, bure, boke aesthetic is still widely employed, many of Provoke’s contemporary cousins make use of an altogether different visual vocabulary. The young Japanese artist Kenta Cobayashi, a self-described digital native, has developed a striking body of work grounded in the language of Photoshop. Whereas for much of its lifetime digital photographic tools were designed to emulate or refine analogue photographic approaches, artists like Cobayashi have begun to explore the possibilities of these tools in order to overtly assert their digital nature. Cobayashi uses his photographs as raw materials, stretching, smearing, and manipulating them into tableaux that reflect the continuous flow of the online digital image.

Provoke’s radical efforts to question photography’s accepted documentary function continue to be of vital relevance today. Fifty years on, photography’s relationship to reality or indeed truth lies in tatters and some of the most interesting work is being made by artists that have chosen to dance on its grave. Like Cobayashi, the American artist Lucas Blalock has made Photoshop’s tools central to his approach. His images appear both crudely manipulated and oddly realistic, artful constructions that nonetheless bear all the hallmarks of “real” photographs. Whereas Provoke’s imagery was often ominous and foreboding, Blalock makes extensive use of humor (a recent show is entitled Low Comedy) in order to engage the viewer with his images which invite us to consider both how photographs are made and how we invest them with meaning.

A similar use of humor runs through the work of Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs, a Swiss duo that has made the question of what photography is central to their practice. With series such as The Great Unreal, they simultaneously display their love for the great photographic myths, such as the American road trip, while deconstructing them in images that reveal just how easily photographs can lie to us.

In the context of the formless digital image, materiality, a central concern for Provoke, has become a fertile ground for many contemporary artists. Through series such as Concrete is On My Mind and Mass, the Japanese artist Hiroshi Takizawa has been exploring the ability of photography to translate the material attributes of its subject. Takizawa has focused much of his work on concrete and stone, attempting to convey its qualities through a series of complex books and installations that create surprisingly weighty and tangible images from fragile photographic reproductions on paper.

In today’s world, Provoke’s desire to develop a new photographic language would undoubtedly lead it to the use of appropriated imagery. In a fascinating exchange between Nakahira and Moriyama published in 1970, Nakahira questions Moriyama on his series Accident and its use of “reproductions of television images or news photographs.” While Nakahira described the series as “tremendously shocking to all of us photographers” he clearly saw this as a path of inquiry rich with possibility. This use of found or appropriated imagery has become one of the most fertile grounds for photographic experimentation by questioning the role of the photographer and author and the meaning of the individual image in the context of the endless flow of images online.

Unlike many other photographic movements, Provoke was firmly grounded in the interaction between images and language, and laid out its intentions in a powerful manifesto. While a photographic collective united behind such a radical statement may be difficult to imagine in the age of the hashtag, many of the ideas articulated by Provoke remain as urgent and vital as ever.