Keep on Taking Photographs for Ever and Ever

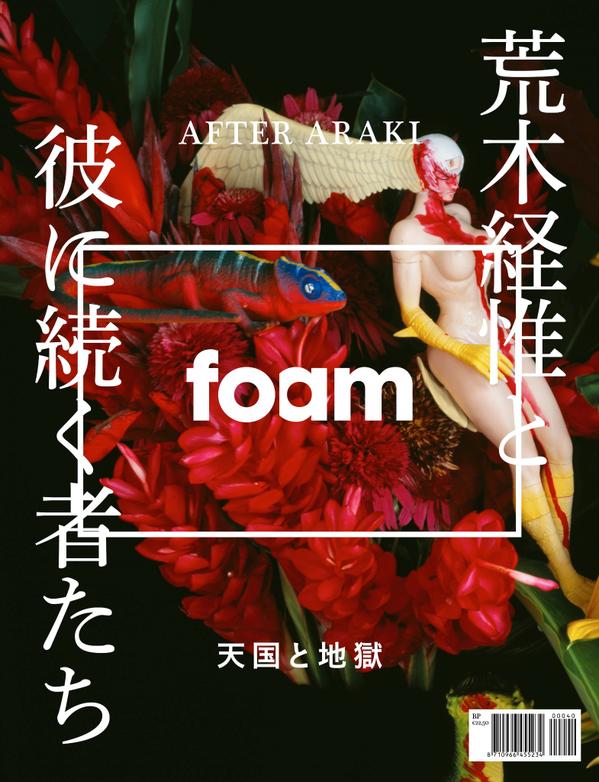

Foam #40, "After Araki," 2015

“Photography is your teacher. The main thing is to keep on taking photographs for ever and ever.”

Nobuyoshi Araki

In the early 2000s, I fell into the cauldron of Japanese photography and have spent the last decade sharing my passion for this country’s extraordinary photographic culture by attempting to increase its visibility in the West. When I began on this path ten years ago, Japanese photographers were virtually unknown in Europe, with two notable exceptions: Daido Moriyama and Nobuyoshi Araki. Thankfully, globalization has caught up with photography and we are now as likely to see work from Japan as we are from a close geographic neighbour. Yet, the influence of Moriyama and Araki remains as strong as ever: if Japan were to award “living national treasure” status to photographers, there is little doubt as to who this honour would be bestowed on.

While Araki is familiar to anyone with an interest in fine art photography, we tend to have a narrow view of this self-proclaimed “photo-maniac.” The discourse surrounding his work can be summed up by the title of an article in the Guardian newspaper, written on the occasion of a 2013 exhibition at a London gallery: “Is Nobuyoshi Araki’s photography art or porn?” The art world’s spotlight has never been fond of complexity and so Araki’s fame—or is it notoriety?—derives almost entirely from his photographs of the traditional Japanese art of bondage (kinbaku).

And yet this photographer from the traditional shitamachi quarter of downtown Tokyo has produced an extraordinarily diverse body of work over the best part of five decades. For those who might see Araki as a kind of jester to the court of photography, take a look at his early work on the brothers Sachin and Mabo, his astonishing Shokuji (The Banquet), or his recent book Chiro Love Death devoted to his beloved cat Chiro that packs the same emotional punch as his much celebrated Sentimental Journey. Araki is not one but several photographers wrapped into one. He is a photographic chameleon, pandering to the crowd in one instant before hitting them with a curve ball in the next.

The most telling illustration of the importance and depth of this artist’s work can be seen in his publishing output. According to the Ararchy Photobook Mania exhibition at the Izu Photo Museum in 2012, Araki produced no less than 454 publications between 1970 and 2012 (a number that must be creeping close to the 500 market at the time of writing).

For these and many other reasons, Araki is an inevitable figure for any photographer working in Japan today. Not only because of the scale and volume of his work and the fact that Araki remains, at 74, an extraordinarily prolific photographer, but also because he is one of the chief tastemakers on the Japanese photo scene, attributing awards, supporting young artists and occupying more than his fair share of the limelight. In addition, the fact that Araki has been synonymous with Japanese photography for so many years leads us to project his influence onto the work produced by any Japanese photographer, no matter how unrelated they might be. Yet, the extent of that influence is a question worth exploring, not only to get a better understanding of this anarchic artist, but also to consider how the ideas he has championed throughout his career manifest themselves in today’s world.

Daifu Motoyuki

Daifu Motoyuki, Project Family

In his 1971 book Sentimental Journey, Araki famously compared his photographic style to that of the I-novel, a literary genre that arose in early twentieth century Japanese literature: “My point of departure as a photographer is love, and it just so happens that I began from an I-novel. (…) That’s because I think the I-novel comes closest to photography.” This form of confessional literature is based on a naturalistic approach, often involving an exploration of the darker side of society or of the author’s life. Daifu Motoyuki’s Project Family clearly operates in this tradition, updated for the everyday reality of twenty-first century Japan.

Of the three contemporary photographers I will consider in this piece, Motoyuki could be Araki’s most direct “descendant”. Born in 1985 in Tokyo, this young photographer has made the most personal aspects of his world the subject matter for his work. In 2005, Motoyuki started taking snapshots of his family home in Tokyo which he shares with his parents and siblings. In 2013 he published a book of these photographs entitled Project Family.

While the idea of photographing one’s residence could not be more ordinary, Motoyuki’s family home is anything but. The mess and clutter is overwhelming. Bags fo rubbish, piles of clothes, half-eaten meals, dirty dishes and empty packaging all jostle for position in an arrangement so dense that barely a single square inch of floor or wall can be seen. His family and the odd pet appear in some of the images, but they fade into the background as every frame is packed with debris to the point of bursting. The photographs could be staged, the aftermath of some natural disaster or of a particularly chaotic burglary, were it not for the vacant expressions of Motoyuki’s family members who look completely at home, oblivious to the clutter that appears to the creeping domestic chaos is steadily gaining on them.

Project Family relies heavily on the snapshot aesthetic that Araki was so instrumental in popularizing amongst Japan’s photographers, as Motoyuki crudely lights up his surroundings with his camera’s flash. The series doesn’t have the overt erotic frisson of Araki’s intimate work, but there is a strangely primal, maybe even sexual quality to Motoyuki’s photographs of this chaotic world. In fact, Motoyuki’s alternate title for these pictures, The family is a pubis. That’s why I cover it with a beautiful panty, could easily have been written by the man who coined the phrase, “The lens is a penis. Film is a regenerated hymen.”

When I first saw Motoyuki’s photographs of his family home, I was immediately reminded of Araki’s 1993 book Shokuji (The Banquet). The series is essentially a close-up food diary, dish after dish pictured in tight close-ups, glistening from the harsh light of the flash. The English title suggests extravagance, but in the original Japanese the title refers to a simpler meal. In fact Araki conceived the book as a tribute to his late wife Yoko, a meditation on the food they shared during the last months of her life before she succumbed to cancer. Looking at Project Family, it occurred to me that this series could be the aftermath of Araki’s banquet, the dirty dishes, empty bottles and discarded fish bones all that remains.

The greatest similarity between the two photographers lies in the central role that love plays in their work. In fact, Motoyuki’s follow-up to Project Family is entitled Lovesody (a contraction of “love” and “rhapsody”). The series is a warm but unromantic documentation of his passionate but short-lived relationship with a pregnant single mother (2014’s equivalent of a honeymoon). A remarkable echo to Araki’s Sentimental Journey with his new bride Yoko over forty years ago.

Momo Okabe

Momo Okabe, Bible

While Daifu Motoyuki may be treading in Araki’s footsteps, both in terms of his subject matter and approach, Momo Okabe’s work occupies a radically different, highly singular space. While this young artist crossed paths with Araki very early in her career—her series As if I were alive was lauded by Araki as part of the New Cosmos of Photography Award in 1999—the connections between their work are of a more superficial nature.

Araki is the ultimate photographic extrovert, a centripetal force that draws the entire world in towards him. He has situated himself at the front and centre of the Tokyo photo scene, both domestically and internationally. Okabe on the other hand is the quintessential introvert, an outsider artist operating on the margins of the photography world.

Like Araki, Okabe was first noticed through a hand-made photo album which she produced in a limited edition of 55 copies. Entitled Dildo, the book explores her relationship with two lovers with gender identity disorder, initially in Japan and then in Thailand where her second partner travels for sex reassignment surgery. While Dildo functions as a private diary, Okabe’s latest project, Bible, builds on the foundations of that first book into a far more expansive work that is all the more powerful for it. In this latest project she has assembled images taken in Tokyo, Miyagi and India over the course of several years.

In both series, Okabe shifts between anodyne images of empty rooms, urban debris, portraits and skylines to graphic images of the body that serve as evidence of a startlingly direct, unflinching gaze. Her greatest strength lies in her ability to weave these two different photographic vocabularies together into a coherent whole that conveys the complexity of her emotional universe. By using marked colour casts with most of her images, Okabe gives an otherworldly aura to her photographs, each hue creating a specific emotional overtone or atmosphere.

While Okabe’s work contains graphic images of the body, it could not be further removed from Araki’s humid eroticism. Hers are not images of sex, but of sexuality and its struggles. There is something much darker at work here, a primal, even animalistic quality which at times can make her work unsettling. These are photographs that are clearly the product of inner turmoil.

This difference stems in part from their opposing views as to the nature of the photographic act. Whereas Araki conceives the camera as a phallic, for Okabe photography serves a healing purpose. She explains how she “discovered that everything looked perfect and beautiful when I looked at the world though a camera.” For Okabe photography is a transformative, even redemptive act, one that enables her “to cope with the difficult situations that happen in life.”

Where the two artists come together is in their remarkable ability to translate their sensitivity to the world into photographs. While Araki can sometimes appear as a mischievous, insolent man-child whose photographs appear as frivolous provocations, throughout his career he has produced his most powerful work when faced with death—the death of his wife and of his pet cat Chiro—and his own mortality. Both artists have the ability to balance sadness and joy, hope and despair in a way that gives their work a rare emotional power.

Lieko Shiga

Lieko Shiga, Rasen Kaigan

Born in 1980, Lieko Shiga is possibly the most distinctive photographic voice to have emerged in Japan in recent years. She came to international attention with her 2007 book Canary, the first articulation of her unique visual style. Shiga’s pictures couldn’t be further removed from the snapshot aesthetic. They are painstakingly constructed, often based on past experiences and memories. Rather than documents of the physical world they feel like photographs of the invisible—renderings of our thoughts, dreams, and fantasies. This unique approach to photography was already evident in Canary, but it wasn’t until Rasen Kaigan that she found a subject that was able to elevate her visual style to a plane of rare power.

In the aftermath of Canary in 2008, Shiga was searching for a new direction for her photography as well as a new place to settle and set up her studio, a process which brought her to the tiny coastal community of Kitakama in Japan’s Tohoku region. Shiga felt an instant connection—she describes the village as “the place I’d been looking for.” Through a meeting with a local association leader, she was offered a position as the official photographer of the community which she accepted immediately. This marked the beginning of her project, Rasen Kaigan (The Spiral Shore).

For several months, Shiga found herself photographing every aspect of life in her new home—local events, personal occasions, portraits for ID photos, fishing parties, a flower in someone’s yard “that only blooms once a year,” the damage to a car from a road accident. She was asked to make prints from locals’ instant cameras, to scan old photos for which the negatives had been lost, to help choose frames and to teach people how to use their own cameras—everything except producing photographs for her personal artistic practice. It wasn’t until a woman asked Shiga to produce a portrait for her own funeral, that her role as official photographer and her personal practice merged.

Over the course of several months, Shiga began to produce a photographic history of Kitakama and its inhabitants. Far removed from a traditional photographic documentation, Shiga was instead trying to convey the spirit or the essence of her new adoptive home. Her project was already well advanced when the earthquake and the tsunami of March 11, 2011 came and destroyed much of the community that had become her home. In the aftermath Shiga returned to her role as the community’s official photographer, setting up a makeshift “laboratory” where she salvaged lost photographs, cleaned, dried them and attempted to return them to their owners.

The story of Rasen Kaigan’s gestation is important to understand Shiga’s commitment to photography. She describes photography as “a space liberated from past, present, and future, a ceremony for that purpose,” and as “a way of searching for a real and honest response and feeling for the real world.” It is in the depth of her commitment to the medium that a bond can be seen with Araki. While Araki made his own life his subject matter, Shiga has chosen to devote her own life to her subjects.

For over half a century Araki has photographed constantly, relentlessly producing possibly the largest body of work of any photographer still working today. Shiga is nowhere near as prolific, each one of her photographs taking days if not weeks to create. But she invests each piece with great significance. Although their approaches are divergent, in opposition even, they share a belief in the ability of photography to convey the essence of its subject.

Situating the work of Motofuki, Okabe and Shiga in relation to Araki, feels like a somewhat arbitrary exercise as there are far more powerful driving factors at play in their respective practices. And yet it is a question that should be considered, such is the extent to which Araki’s work has shaped our understanding of the photography produced in Japan.

When I asked Shiga what Araki’s work meant to her, her answer struck me as the perfect description of the way her generation experiences his legacy. Rather than speaking of a specific image or body of work, she told me that for her, the most important thing was the “quantity of the matter of his photographs. Sometimes, when I am walking through the city, I find a scene that is like one of his photographs. At that moment, I feel that the world of photography has flipped into the real world.” Araki’s direct influence will surely fade, but the world that he has created over five decades will remain one of the great photographic landmarks.

By Marc Feustel