Interview with Thomas Mailaender

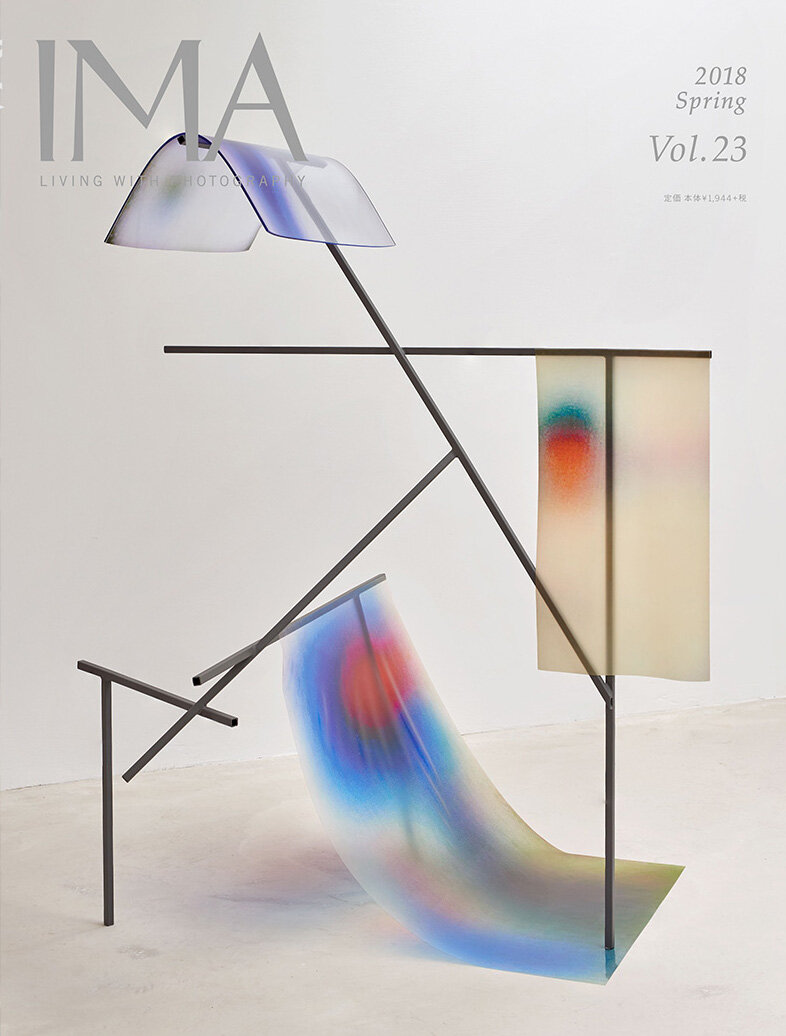

IMA, Vol. 23, Spring 2018

For IMA magazine’s “How They are Made” column, I interviewed the French artist and provocateur Thomas Mailaender about his practice and how is huge studio space influences his work.

Since he installed a chicken museum in the flagship exhibition From Here On at the Rencontres d’Arles in 2011, Thomas Mailaender has made a reputation for himself as the gleeful prankster-in-chief of the European photography scene. A cross between an artist and a collector, Mailaender is equally as fascinated by the trashy disposable images he digs up online as he is by esoteric photographic artefacts found at flea markets or yard sales. His studio in Asnieres on the outskirts of Paris—a 4,000 m2 former printing factory which he shares with a group of around 30 other contemporary artists—acts as a laboratory for his grand, but never too serious artistic experimentation.

In all of your work you integrate images you have collected over time. How did you start building your archive?

When I started out, I took pictures myself, experimenting with different cameras. There came a point in the early 2000s when I was drawn to a certain kind of imagery that I was not able to make myself because these were images that needed to be made by amateurs.

With the advent of the smartphone, I also found myself questioning whether the world needed more photographs. It was almost like an ecological approach: why create more photographs when we can reuse and recycle all of the images that have already been made?

So I began to collect images on blogs or online forums to constitute what I call the Fun Archive. I see them as the digital equivalent of postcards: a little gift that we send to someone to let them know that we’re thinking of them or make them smile. I wanted to collect these images and to keep a trace of them, to archive them as they would otherwise disappear through the process of digital decay.

When did you start doing this? Before social media really took off?

Around the year 2000. Many of the places where I went to find images are disappearing now. I’m far less interested in doing that exercise with Instagram today.

I liked the idea of the end of an era and of being a kind of “pioneer” of the digital era. But with Instagram, I feel like the image sharing thing has become kind of monstrous. When you take the metro in Paris and see a carriage-full of people all scrolling down on their phones, I find it more depressing than anything else. At this point, I’m not really adding to this archive of web images anymore. So maybe I’ll start taking pictures again (laughs).

Alongside the Fun Archive you have also built up a collection of photographic artefacts and objects called the Fun Archeology. Did you start building these two archives at the same time?

Yes, it was at a time that felt like a turning point, the end of an era and the beginning of another. I was interested in exploring both of these eras through the process of collecting.

The Fun Archeology is made up of prints, documents and objects. I go to the Saint Ouen flea markets outside Paris to look for things and a big chunk of what is being sold is the belongings of people who have just died. Up to three or four years ago, there were still prints in these collections of belongings but that is becoming less and less common. People just don’t really have physical photographs anymore.

The Archeology includes a lot of photo-albums for example. I’m fascinated by the way people put together groups of images, from Russian soldiers to a Moroccan snake charmer. They seem to be able to encapsulate a particular historical moment while being funny or satirical at the same time.

How do you use these archives in your work?

In terms of the Fun Archive, I have collected around 10,000 images at this point. I’ve done a series of books with RVB Books using different groups of images from the archive. The first of these, SOTP, was a collection of images of mistakes in road markings. I also use the archive to create objects, for instance by creating a little narrative through the juxtaposition of a few different images.

As for the Fun Archeology, that is based more around an emotional response to these objects, and the desire to preserve them.

You make use of a lot of traditional techniques—from ceramics to cyanotypes—which could seem counterintuitive given your interest in popular culture imagery. Where does your interest in these techniques come from?

Alongside my photographic practice I’ve also worked with ceramics for a long time. Like photography, ceramics seems to be stuck somewhere between craft and art. When I started thinking about integrating photography into ceramics, I did some research and found that there were techniques for doing this. Looking into the history of these techniques, it seemed to resonate with the obsession photography has for conservation, for creating the most durable image possible. I liked the idea of using some of the most disposable images possible in conjunction with a process that can make them last for hundreds of years.

It’s interesting because there is a thrown-together, off-the-cuff feel to your work, but you often use quite complex processes.

When it comes to making work, I like to be quick and spontaneous, but there is a lot of research that happens first. With that said, I like giving people the impression that I have no idea what I’m doing and that I’m just a lunatic. I like playing with those codes of the art world that require us to place work in a conceptual framework and to explain it to the audience.

I was surprised to discover how big your studio space is, which is really uncommon in Paris. How do you make use of all this space in your work?

I have an office in the 18th arrondissement which is where I do most of my archival work. This studio space is focused on production and I like to use it to give a kind of grandiloquence to some of my work. For example, two years ago I made the biggest cyanotype in the world here. We made a kind of cyanotype swimming pool in the studio which acted as a gigantic darkroom for cyanotypes. The scale of this space allows me to take these traditional processes and push them to the extreme.