Interview with Jabulani Dhlamini

IMA, Vol. 34, Winter 2020

For volume 34 of the Japanese magazine IMA, I interviewed the South African artist Jabulani Dhlamini. Here is an excerpt of our conversation:

Your most recent project “The everyday waiting” deals with the COVID-19 pandemic. How did you begin working on this project?

I have been working on a long-term project on the Soweto Uprising [of 1976] for around ten years now. Although I grew up in Soweto, this project has allowed me to see the township from a different point of view. At one point, I moved away and when I came back, I started noticing a lot of things that have been inherited from the apartheid system and how much hasn’t changed since 1994.

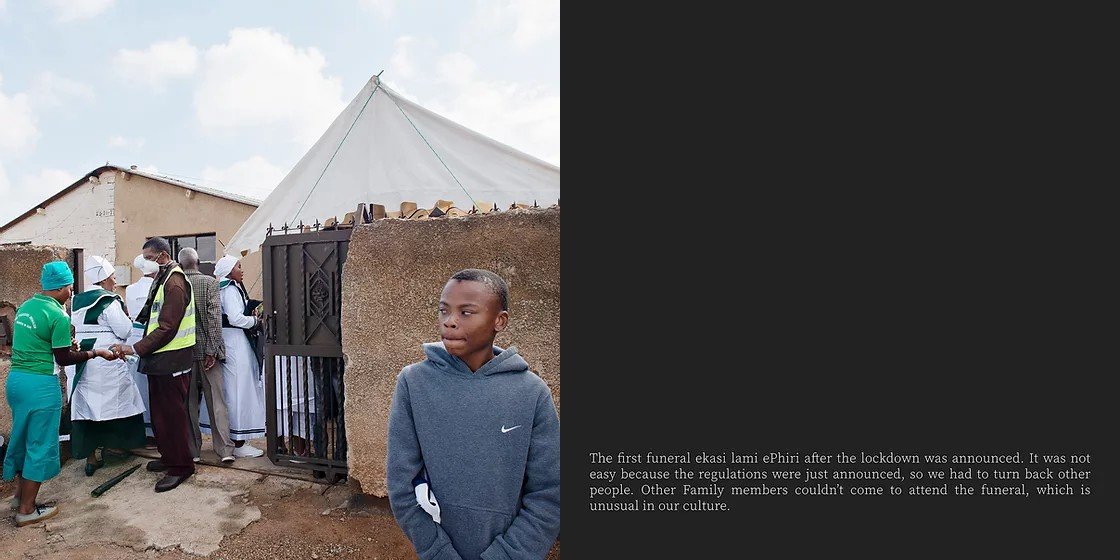

When we first started hearing about the coronavirus and the lockdown was announced, we didn't know what to expect. I started driving my mother to the pharmacy where she worked and while doing this, I began striking up conversations with people in their homes, through their fences or over the walls. That is how the project started, based on these conversations. The aim was to create a platform for us to exchange our feelings about this very uncertain situation.

However, I was not permitted to take photographs, but only to drive my mother to work. So I had to remain in my car. Soweto was militarized with many soldiers and police in the streets. There was a lot of brutality. Photographing from my car became a safe way of operating and allowed me to maintain distance from the people I was photographing. As a documentary photographer, I rely on my ability to relate to the people I am working with, but due to COVID-19 that wasn’t possible.

You mentioned becoming aware of what has been inherited from the apartheid system. What is it that struck you in particular?

The current situation brought forth just how much we have inherited from the apartheid system. For instance, the houses in the townships have not changed since apartheid times and now, you might have 3 or 4 families in a two-room house. That makes isolating very challenging. In South Africa, those that are suffering the most from the pandemic are the black communities because of the inequality that is still so clear today.

The murder of George Floyd in the US and the subsequent Black Lives Matter protests that spread around the world have brought many of these racial issues to the fore. For a country with a very difficult racial history, what has the South African perspective been on these events?

I think that these protests made people aware of things that they thought of as normal or had stopped paying attention to. For instance, my mother’s twin sister is a domestic worker for a white farm owner in a rural area. I remember one occasion when I was visiting her and we needed a lift from the farmer into town. She referred to him using the word ubasi, a word which was used during apartheid times. That made me reflect a lot. Even twenty-five years after apartheid, the privileges of the regime are still in place.

This made me ask myself, how do you liberate someone’s mind who has been oppressed for fifty years? The conversation I wanted to start was about that. Also, what is the farm owner’s contribution? If they leave things as they are and continue to profit from these advantages, how can things change?

What role do you think photography can play in relation to these issues you have mentioned?

I want to draw attention to the people in the townships of Soweto or in other rural places, people that otherwise are not seen or are forgotten.

In some way, I want to decolonize the way that photography is used. I recognize that photography has limitations and often does not afford much freedom to the person being photographed. That is why collaboration is so important to me in order to better tell people’s stories.

I also feel that many people today avoid speaking about these issues. They become accepted, part of what is considered normal. I want to use photography to challenge this. My approach is not to provoke in a confrontational way, but rather, through photography, to create conversations that we need to be having.

From what I see in South Africa, people are still trying to avoid these discussions. And the manner in which they take place here is problematic—they only happen when people are angry, when there has been a tragic event. I don’t believe in that: these are conversations that need to be happening more generally in order for the narrative to change. They are not a one-sided game only for the benefit of black people, they are going to benefit everyone.