Ryudai Takano, ca.ra.ma.ru

(Stockholm: Libraryman, 2022)

I wrote a short essay for Takano Ryudai’s book ca.ra.ma.ru, which revisits one of his early series:

“Maybe in our bodies there’s a whole world of mythology? Maybe there exists some sort of reflection of the great and the small, the human body joining within itself everything with everything.”

Olga Tokarczuk, Flights

Stretching back to the late 1830s, the nude is one of photography’s earliest genres. Yet despite its longevity, it has evolved little over time, remaining governed by three central tenets: the drama of black and white is preferred to more naturalistic color; it is primarily the female body that is depicted; and finally, whether the body is male or female, the nude photograph is almost always made by and for the male gaze.

With ca.ra.ma.ru, one of his earliest bodies of work, Takano Ryudai took a first step onto a well-trodden and often overly narrow path. Photographed in multiple sittings—or rather performances for the camera—over the course of three years, the series began from a simple premise: an invitation by the photographer to a group of Butoh dancers to embody karamaru (to be entangled). He provided no further indications or instructions, allowing them to find their own way into this idea.

As entanglement does in English, the Japanese term karamaru has multiple meanings, from its most literal definition to a connotation of emotional involvement. However, by repurposing the word, replacing the “k” with a “c” and using periods to break it up into its four component phonemes, Takano has slowed down and softened it, giving it an unctuous texture and sweet taste, like the caramel of its Japanese homonym, karameru.

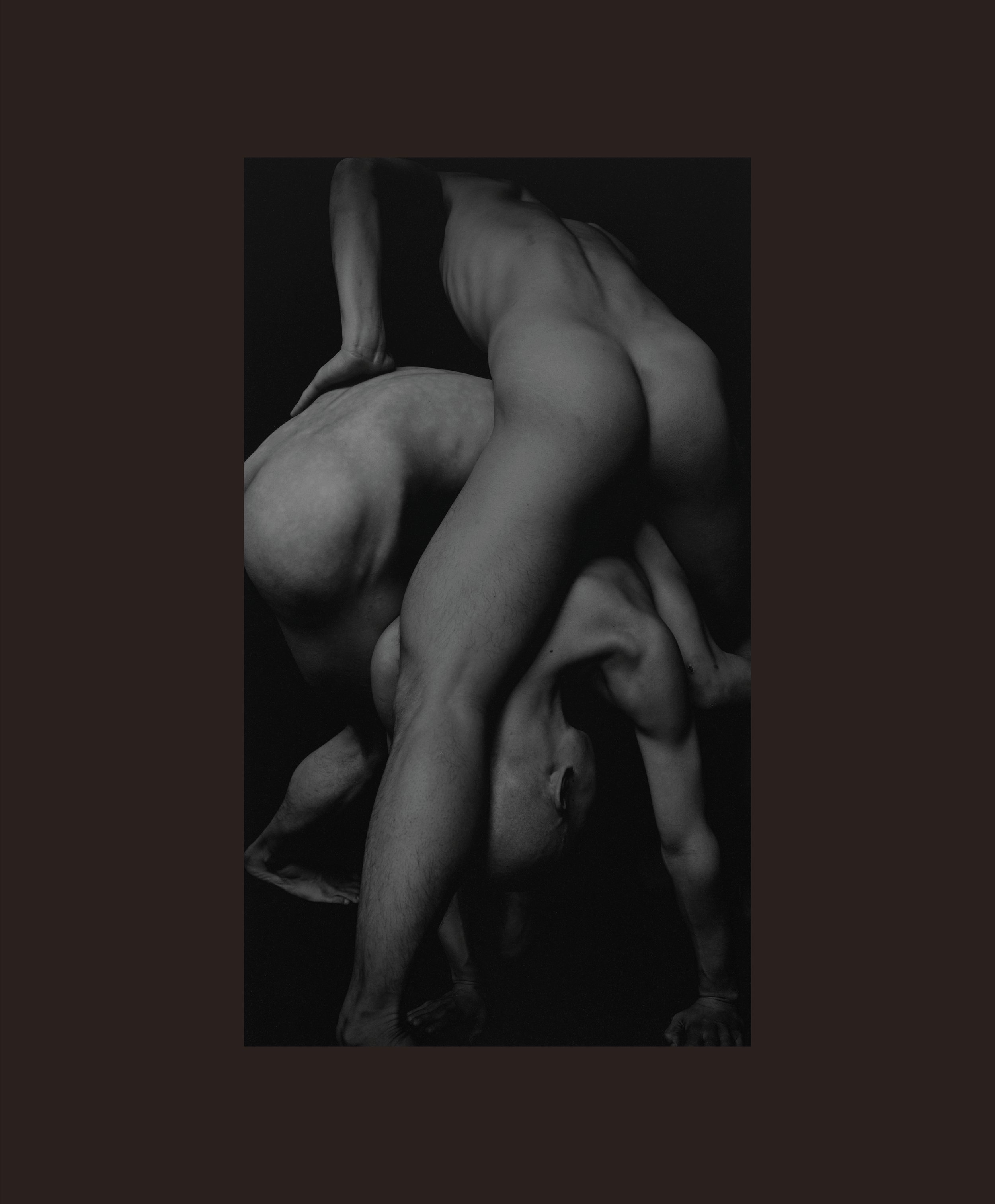

In aesthetic terms, these images are very much in keeping with the classical conventions of the nude—chiaroscuros full of diffuse light and deep shadow. As the performers come together throughout the series, different emotions and sensations come to the surface. At times their bodies are contorted, writhing in pain, muscles taut, limbs knotted inextricably together. At others, they seem to envelop each other with tenderness, skin brushing gently against skin. Some of the performers’ choreographed poses are complex, incomprehensible to the eye, while others appear more natural, human forms that are made to fit together. In a departure from convention, the bodies here are male and female, sometimes appearing separately, sometimes together. But rather than making us aware of this balance between the masculine and the feminine, what is most striking here is that it becomes difficult to tell them apart, or indeed to notice the difference between the two. As Takano says, his search was for the “beauty of the body that transcends the normal images of ‘man’ and ‘woman’ that has been firmly established in society.”

These images were made some thirty years ago, by a young photographer who was still finding his way into his practice. However, as is often the case with photography, they have become more resonant over time. Today, the desire for emancipation from the established—and mutually exclusive—ideas of the masculine and the feminine which is at the heart of this series has become central to a new generation’s search for identity. ca.ra.ma.ru suggests a new mythology of the body, one that transcends the masculine and the feminine, where we are not only entangled with each other, but with the world itself.