Choosing words to go with photographs is a big issue for us photobloggers. Some of us avoid them, others use them with caution, and some, like me, can't seem to hold them back. Choosing the right balance between words and images is a very tricky thing and this tightrope walk often makes me think about the power of captions and titles in photography.

On his NY Times blog, the film-maker Errol Morris has been writing recently about the idea that photography can somehow translate some objective truth. In one post he focuses on the issue of the caption in relation to photojournalism, showing how a caption can lead to radically different, if not opposite, interpretations of the same image. Morris's example is a little too black-and-white for my liking, but it does provide an extreme example of just how easy it is to modify the way that an image is interpreted by the viewer through its caption.

In the world of fine art photography, the caption is less ubiquitous than in photojournalism. In the former the image isn't required to fulfil the function of conveying specific information. In fact I am most drawn to photography which tries to not have a specific message: images which raise questions or evoke possibilities rather than images which try to show the viewer something. I have written about this before in the context of Ken Domon and Kikuji Kawada or Shomei Tomatsu's radically different approaches to photographing the aftermath of the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But even for the 'subjective documentary' of Kawada or Tomatsu their photographs still had some form of documentary function and their titles or captions were written to give the viewer factual information about the contents of the image.

In much fine art photography that documentary function doesn't exist or is consciously avoided. And yet the issue of choosing a title for the image remains, even if only to be able to archive or catalogue a series of images. In this context, I know that a lot of photographers struggle with the process of giving titles to individual images, precisely because they want them to remain as open to interpretation as possible. One photographer told me that he didn't want to give his work titles but that his gallery talked him into it for sales purposes. (On this note, I recommend checking out Olivier Laude's portfolios for a terrific subversion of the often ridiculous text that works inherit when they are released into the art market). And so images are reluctantly given titles or more often just join the brotherhood of the 'Untitled'.

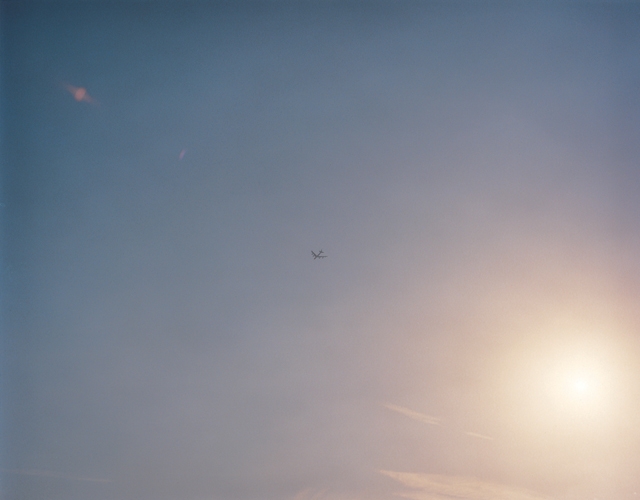

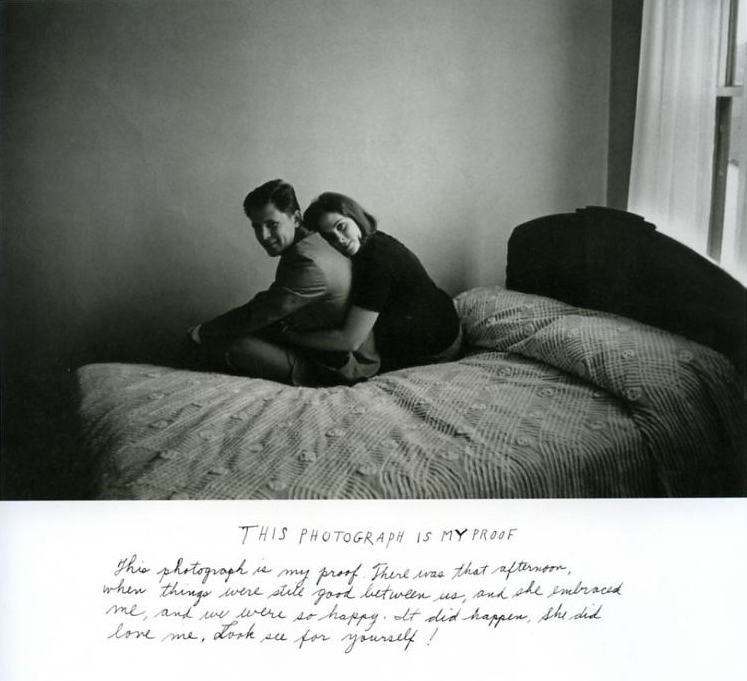

However, for some photographers the caption is crucial to their work. Tomoko Yoneda is a Japanese photographer based in the UK who uses captions very effectively to transform her images. A large part of her work centres on major historical events and Yoneda uses captions to invest extremely banal scenes with great significance (see the picture above). In her work captions are able to invest a single photograph with a profound sense of the history of a place. Her work is the perfect illustration of how what you see is most definitely not what you get. For Duane Michals, one of the highlights of last year's Rencontres d'Arles festival, it sometimes feel like his photographs are there to illustrate his writing rather than the other way around. He uses writing and images together to construct narratives that somehow manage to be both hilarious and sincerely profound. By writing his captions on his prints by hand, he makes the text and the image inseparable.

Another great illustration of the transformative power of a caption is the website Unhappy Hipsters. The site is a series of shots taken from interior design or architecture magazines with added captions describing the existential angst of the people that appear in these pictures. Beyond the fact that I find it frequently hilarious, the site shows how a caption can completely change the way that we read an image. In the context of a magazine like Dwell, the focus is squarely on the architecture and design; the people are mere accessories to dress the space. But with these captions, the roles are reversed: the image is no longer about some material consumption but about human emotion.

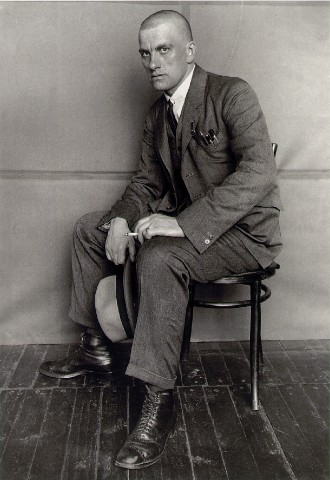

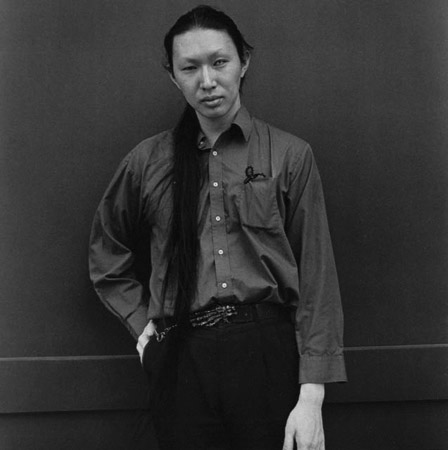

But my favourite use of captions in recent times has to be in Hiroh Kikai's portraits. In an interview with Kikai he told me that he sees his captions and his images as "intrinsically linked". What makes them stand out to me is their ability to suggest a huge amount with a great economy of language. Sometimes just by describing a person's profession ("A bookbinder"), a detail in the picture ("A man with four watches") or even outside the frame ("A man using a wooden sword as a walking stick"), or indeed from a different moment than the frame itself ("A young man about to make a peace sign for the camera"), Kikai gives just enough information to set off questions in our minds which bring these people to life.

Of course, I'm not suggesting that all photographs need captions; actually in my view there's nothing worse than a throwaway title. But the caption is an art form and online, where images get cut and paste all the time without much attention paid to titles, captions or even the photographer's name, one that is too often overlooked.

I've decided to launch an eyecurious offshoot over on tumblr:

I've decided to launch an eyecurious offshoot over on tumblr: